Theodora Allen “Saturnine”

Images by Mikkel Kaldal.

On a summer evening in July 1610, under the humid Padua sky, Galileo peered through his crude telescope to discover the rings of Saturn, the furthest planet then known. While Galileo set his sight on Saturn, it came into view slowly. Ancient Greek and Roman theory, and later medieval psychology, had correlated four planets with each of the elements and temporal ‘humours’; Jupiter’s persuasion prevailed in the blood and affected a sanguine nature; Mars ruled aggression; the moon was cause for an apathetic disposition. The fourth and final humour, inspired by ringed Saturn, was responsible for melancholy. It is for this reason we have the term ‘saturnine’ to describe sadness. The sight of Saturn is one of sorrow.

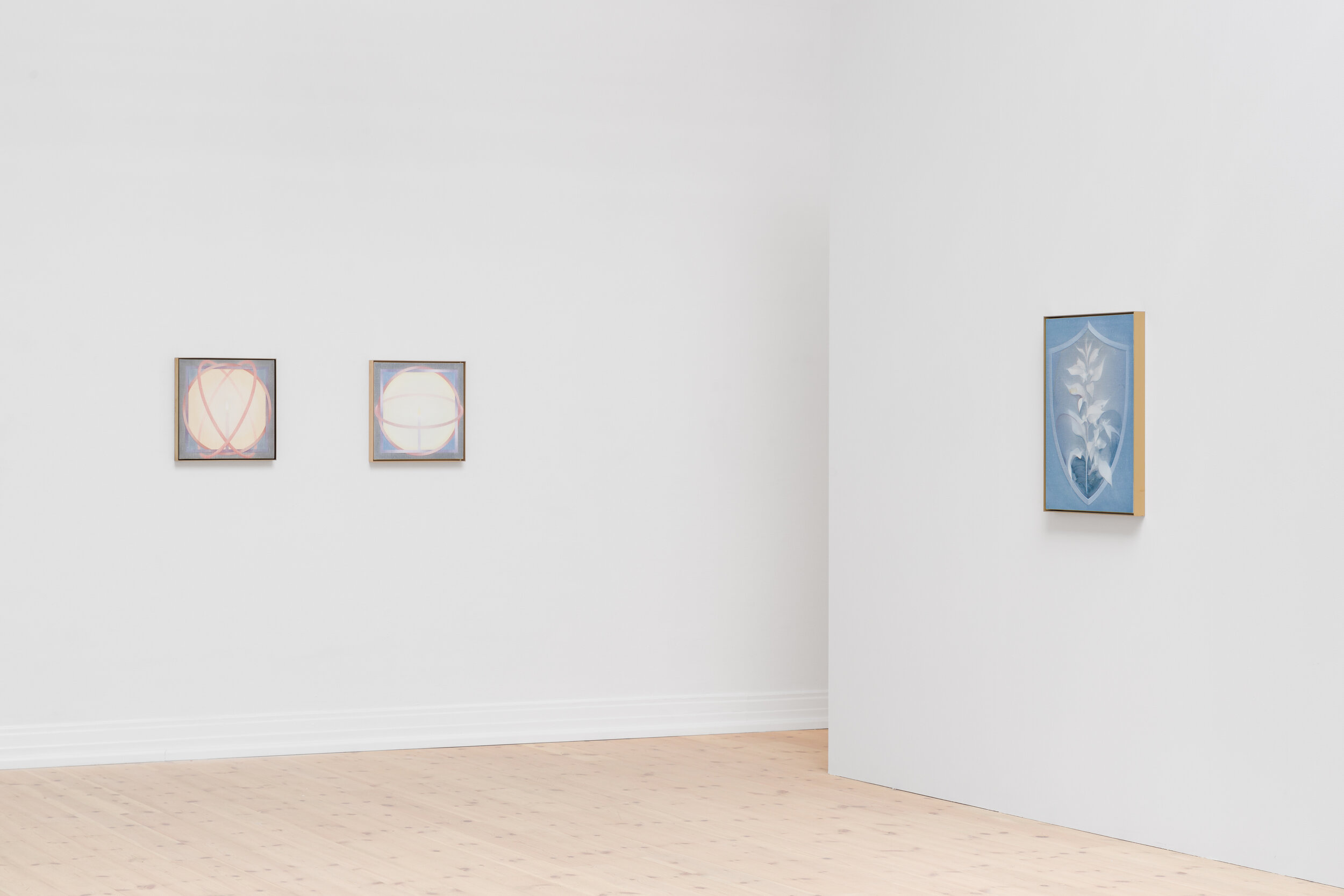

Kunsthal Aarhus presents Saturnine, the first institutional solo exhibition of Los Angeles-based contemporary artist Theodora Allen. Interweaving the artist’s emblematic use of symbols, the exhibition engages with a history of Saturn, the celestial body said to have been the cause of a melancholic disposition – from ancient myth and the Middle Ages through to the present. At times appearing as itself, a large ringed orb, and at others as affect, the figure of the planet joins Allen’s representations of recurrent motifs that are informed by cultural and emotional influence.

Alongside Saturn, depictions of markers such as serpents, wildfires, moths, hourglasses and hallucinogenic plants present a language that is seen rather than uttered. Within the emblematic tradition – a form positioned squarely between visual arts and literature, grappling equally with both image and text – Allen’s compositions exist as propositions of impossibilities. As concepts, they transport the viewer elsewhere: into different times, different narratives. Steeped in mythmaking and iconography, the paintings are resonant with the visionary work of poets and painters in early Symbolist graphic arts, as well as resurgences of this aesthetic in the zeitgeist of 1970s California, addressing cyclical, enduring themes of human versus nature that withstand in our contemporary moment.

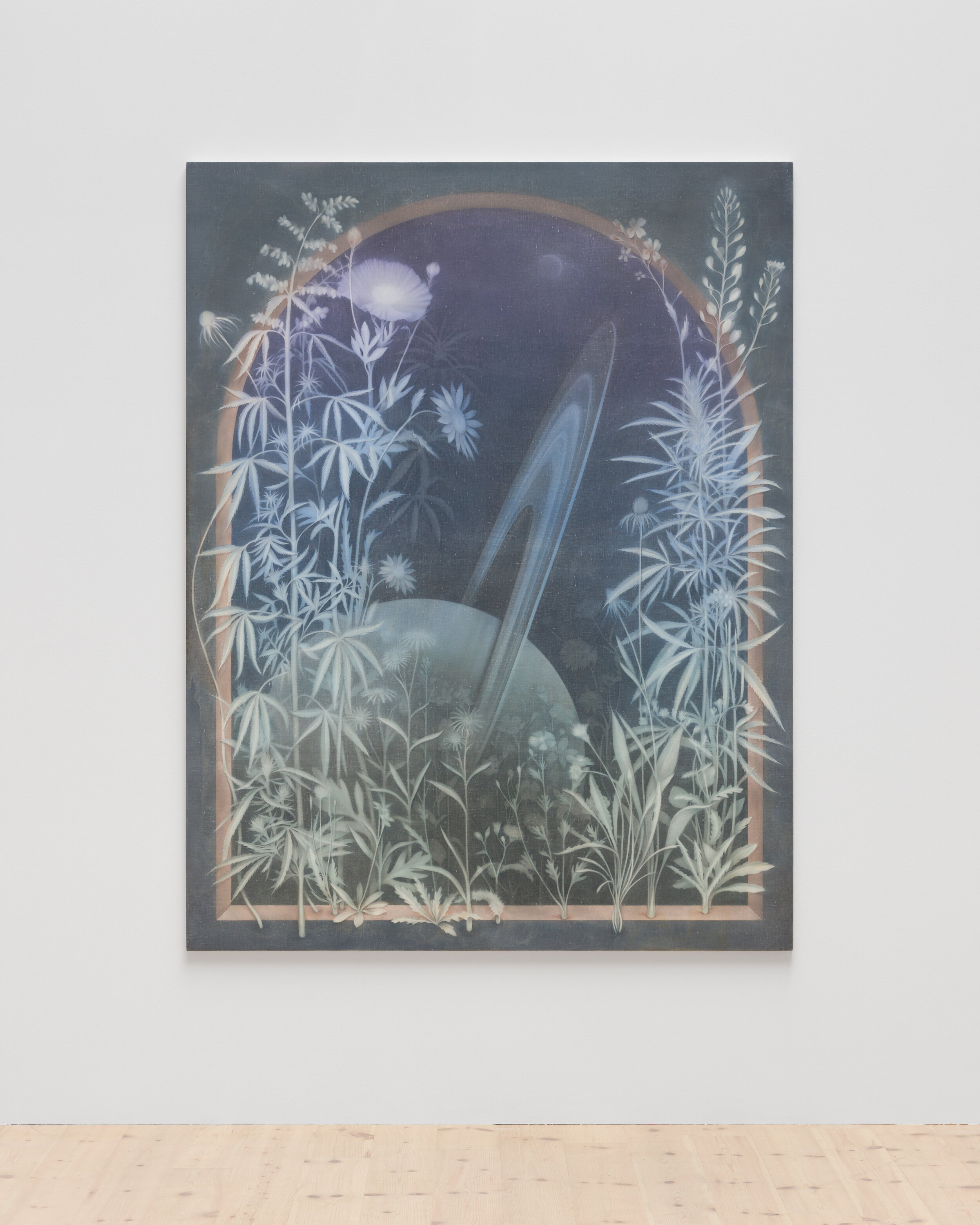

In The Cosmic Garden I (2016), the image of a fallen Saturn is framed within an arched window, a classical compositional element that alternates between the foreground and background of the painting. The planet appears to be diving ever deeper into the landscape – painted in hues of indigo, lapis, emerald, gold, and grey – is surrounded by delicately depicted wildflowers. The image of a planet close enough to touch suggests the possibility of tactility. Running your fingers along its rings, would they be sharp like the edge of a circular blade, or as soft as grains of sand, dispersing by the touch of your hand before reassembling by some force of gravity? The painting appears to glow; pictorial elements reveal themselves slowly, like your eyes adjusting to a night sky when you are far away from the light pollution of a city.

The modulation of the artist’s ethereal images come into being through a process of removal and regeneration; paint lifted off a darkly covered surface to reveal the ground of white behind the pigment before introducing more sheer layers gradually polluted by the addition of color, tone, and opacity, as well as the ground itself. This paradox – the creation of an image through a means of subtraction and alteration – is at the core of the aesthetic affect achieved across Allen’s careful output. A strategy of ‘dimming’ the light source that mediates between presence and absence.

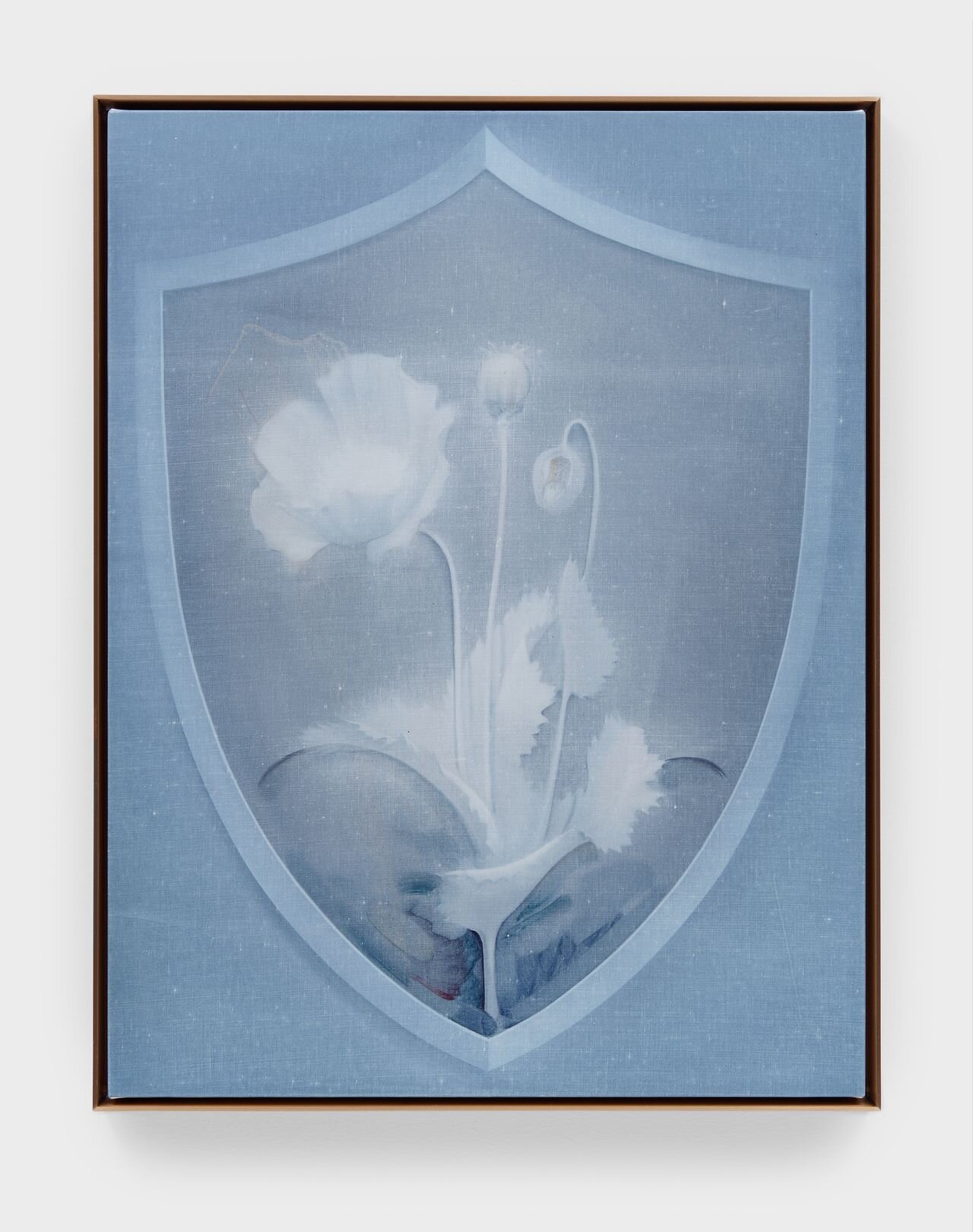

Among the hallucinogenic flora featured within two works from Allen’s Shields series, we see the opium poppy and belladonna. The dark berries of the deadly nightshade, whose poison was once used to dilate women’s pupils during the Italian Renaissance (in the name of beauty, most went blind), and the deep flush of the black-centred poppy (responsible for numerous drug wars) are both reduced to the same light emanating blue. Reminiscent of process cyan, or a film negative, the paintings hover between the soft silvery rendering of moonlight and the redacted shadow of a negative image produced by early photography. Their manner of representation is either too detailed, or too abridged, to nest comfortably in either category. In both, the psychotropic plants – killer or curer, sinner or saint – are presented as objects of protection. For the melancholic, known as the ‘curse of artists’, this protection meant the freedom of being exposed to obsession, or madness, in order to reach a state of artistic genius. The antidote was the poison, a therapy of curing same with same.

The moth flies closer to the flame.

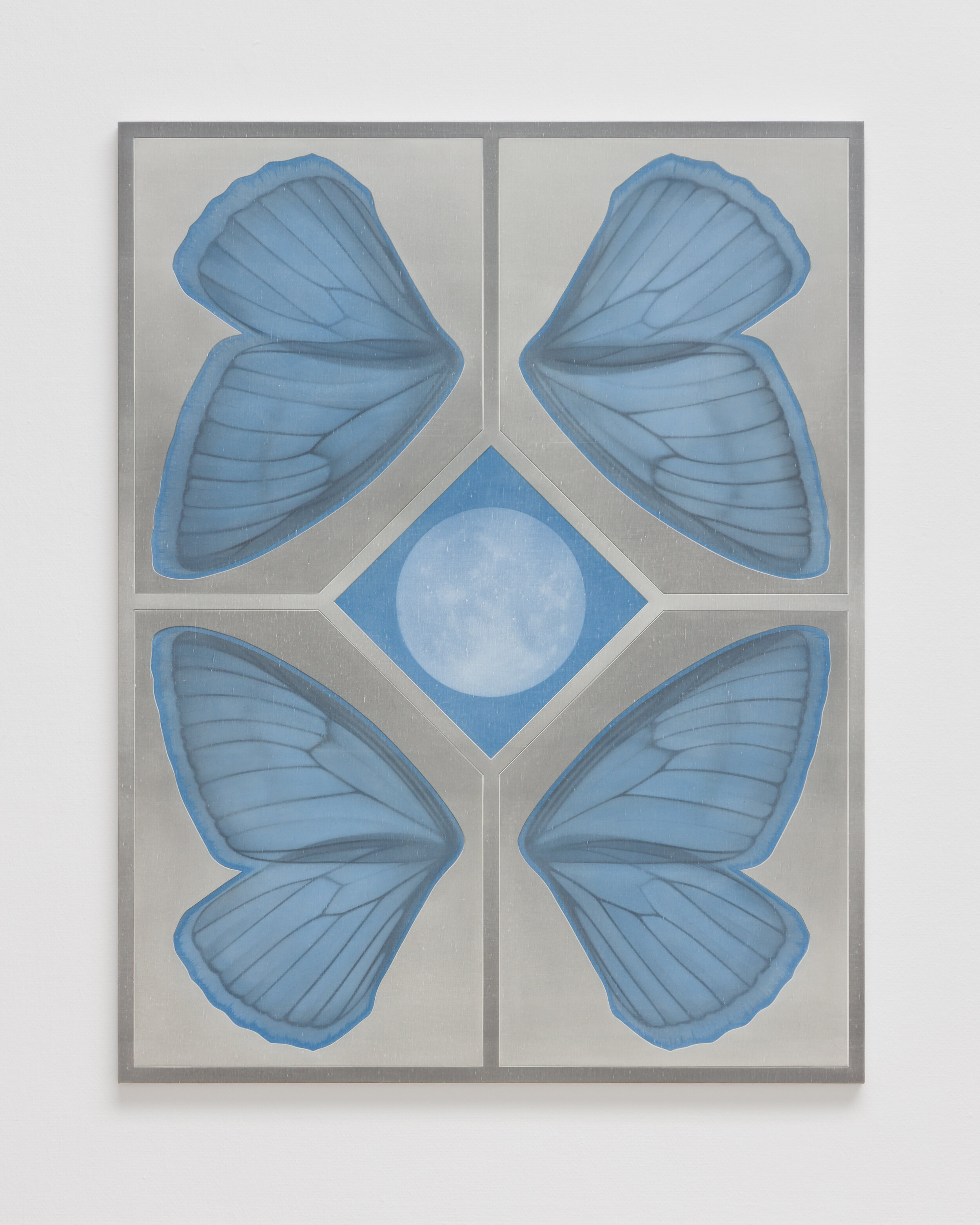

From the Watchtower (Double Moth No. 5) (2020) pictures two sets of moth wings set into a quadrant whose grey field frames a diamond in the centre of the canvas. Within this geometric porthole, a full moon – low contrast and underdeveloped, such as one that would be seen against the bright sky of daylight – carries a gemstone-like quality, opalescent and glinting, against a frame that appears to be carved like die-cut metal. Occupying the rear space of the galleries, this painting joins Allen’s most recent body of work from the Life Thread series, made for the exhibition. Presenting large-scale machine bolts, centred within the picture plane as both figurative subjects and architectural supports, the hardware acts as a barrier and also a passage. Rising like columns, the spiralling physique of the bolts are framed by either datura (known as jimsonweed, devil’s snare, or moon flower) or morning glories (known as ‘Heavenly Blue’), pale-petaled vines similarly twisting to find their light. Speaking on the subject of Allen’s Shields and touching on the plants’ folkloric, historical and contemporary significance, the artist writes, ‘They were medicine, sacraments, poisons of the old world; uppers, downers, and narcotics in the new one’. The potentially deadly plants, once used as aphrodisiacs or alternatives to LSD, replace the emblem of armour and protection with that of a dialectic – death or love in equal measures.

Like the rings of Saturn to its sphere, Allen’s work orbits around representations of melancholy in visual culture. As singular images, her paintings communicate the hyper-relevant present through outmoded representations of the past. Transforming legend into history, Allen’s use of emblems is aligned by a fin de siècle desire to ‘bring the past up to meet us’ – a way to carry certain values into a future. In the twenty-first century, a Southern Californian analogy is the choice of selecting a few things from your house when evacuating from a wildfire.

What will you save, what will you bring with you?

Alternating between fictional texts and critical essays, an accompanying catalogue published by Motto Books, Theodora Allen: Saturnine, will be available on the occasion of the exhibition.

Text by Curator Stephanie Cristello.