"Taurus the Awakener"

Taurus and the Awakener takes its title from the astrological lexicon, and makes reference to the recent ingress of the planet Uranus into the zodiacal sign of Taurus. In his 1995 book Prometheus the Awakener, cultural historian Richard Tarnas describes how astrologers have come to associate Uranus with “change, rebellion, freedom, liberation, reform, revolution, and the unexpected breakup of structures; with excitement, sudden surprises, lightning-like flashes of insight, revelations and awakenings.” Suggesting that the planet was misnamed, he instead connects its archetypal terrain to the myth of Prometheus, who disobediently stole fire from the gods in an egalitarian act of technology-sharing.

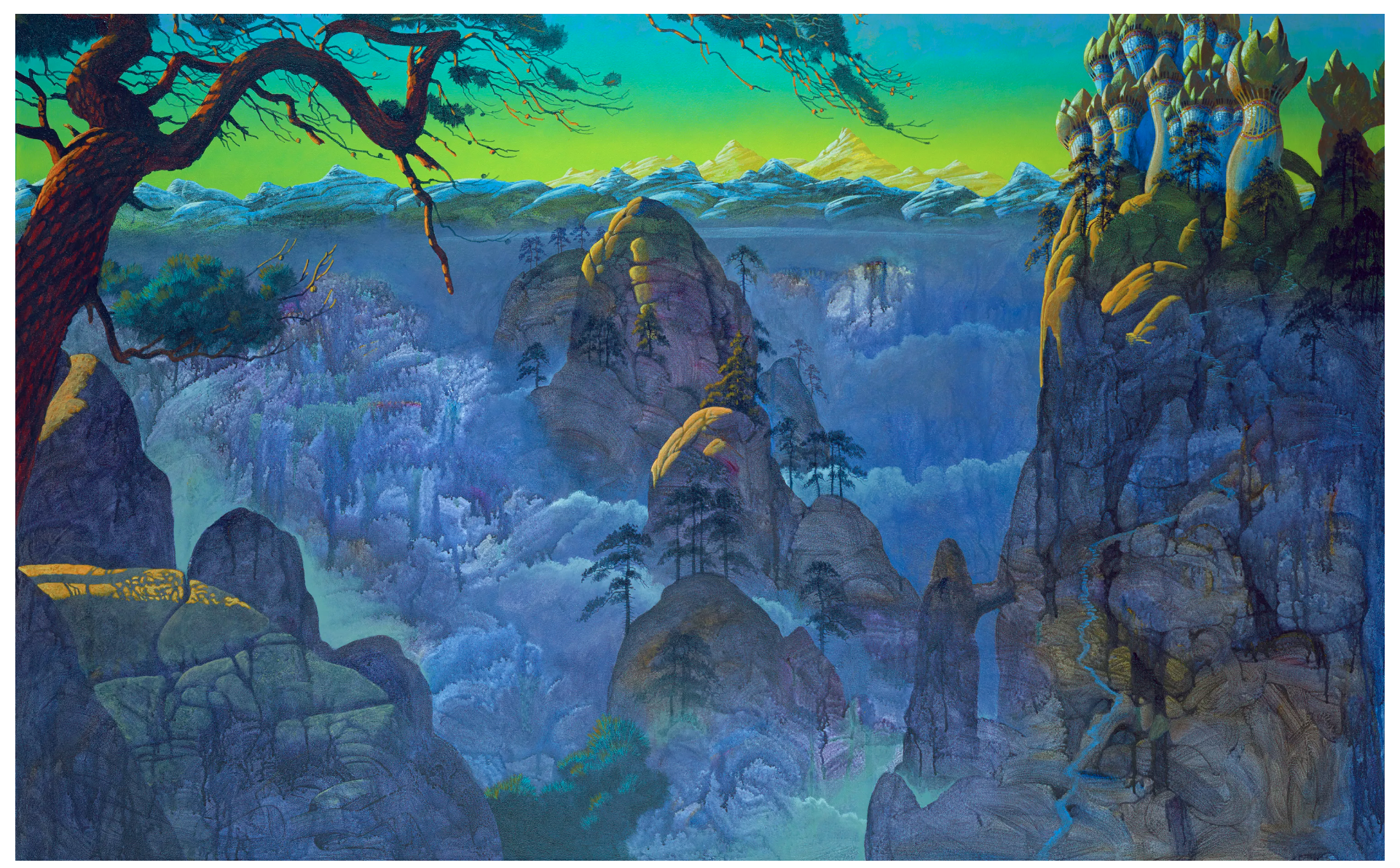

Uranus entered Taurus in May 2018, and will remain there, save for a brief return to Aries later this year and early next, until July 2025. Taurus, as a sign whose symbolism is related to the sensual, the earthy, the grounded, and the fecund, would seem to counteract the excitability and ruthless penchant for innovation that define the Uranian archetype. But combining their themes conjures visions of radical natural structures and an eclectic, searching femininity that inspires a distinctly embodied form of sense perception.

It is this spirit that Taurus and the Awakener seeks to channel by juxtaposing sculptures whose intellectual rigor and experimental ethos are inextricable from their physical expression. Materials used to make the works on view include glazed clay, tires, cigarette packs, incense, dyed velvet, bronze, and broken mirror. They are alternately imposing, ephemeral, dimensional, and provocatively flat; some explode with–or explode as–psychedelic bursts of color, while others rely upon subtle and brooding variations of hue to bring out the intensity of their textures. Rich in concepts articulated via non-linguistic modes, the exhibition teems with intricate patterns and esoteric geometries.

These broader formal considerations are rooted in conversations that emerge between individual works. For example, the intense, monumental presence of Chakaia Booker’s sculptures built from sliced tires, which function as wide-ranging metaphors for a host of social and environmental conditions–labor, race, class, urban development–enter into idiosyncratic dialogue with the assemblage constructions of Paul Pascal Thériault, in which constellations of cigarette packs and other found materials are perched on shelves or pedestals. Both artists bring new life to discarded objects by subjecting them to an abstract sense of order.

Polly Apfelbaum reformulates the category of the monumental altogether in a sprawling floor-bound work composed from quantities of dyed fabric pieces. Essentially a horizontal painting, it nonetheless has a distinct materiality that allows it to keep some of its many feet in the realm of sculpture. Such dismantling of genre divisions is a recurring theme. In an example from Betty Woodman’s Aztec Vase and Carpet series, a large-winged ceramic vessel rests on a piece of canvas layered with flat ceramic fragments; all elements have been glazed or painted with bright colors and patterns so that they unify in a Cubist-inspired tour de force of spatial illusion and visual rhythm. Ruby Neri, whose contributions to the show also come in the form of ceramic vessels, produces boldly Venusian images of the female body, glazing the undulating sides of large pots with relief paintings of women in Dionysian revelry.

The human–or humanoid–form plays an equally important role for Huma Bhabha. Her hybridized figures take many shapes, with some immediately recognizable as people or creatures, and others built from rough-hewn, harder-edged, modular components; what unites them is their mysterious emotional availability. Mindy Shapero’s totemic sculptures, with their psychedelic vortices of rainbow color, retain human warmth even when they depart completely from figuration. In one new work, two sizable interlocking circles, covered with swirls of puffy paint and reflective shards, are like the rings of planets, or rings of smoke blown by a fanciful deity.

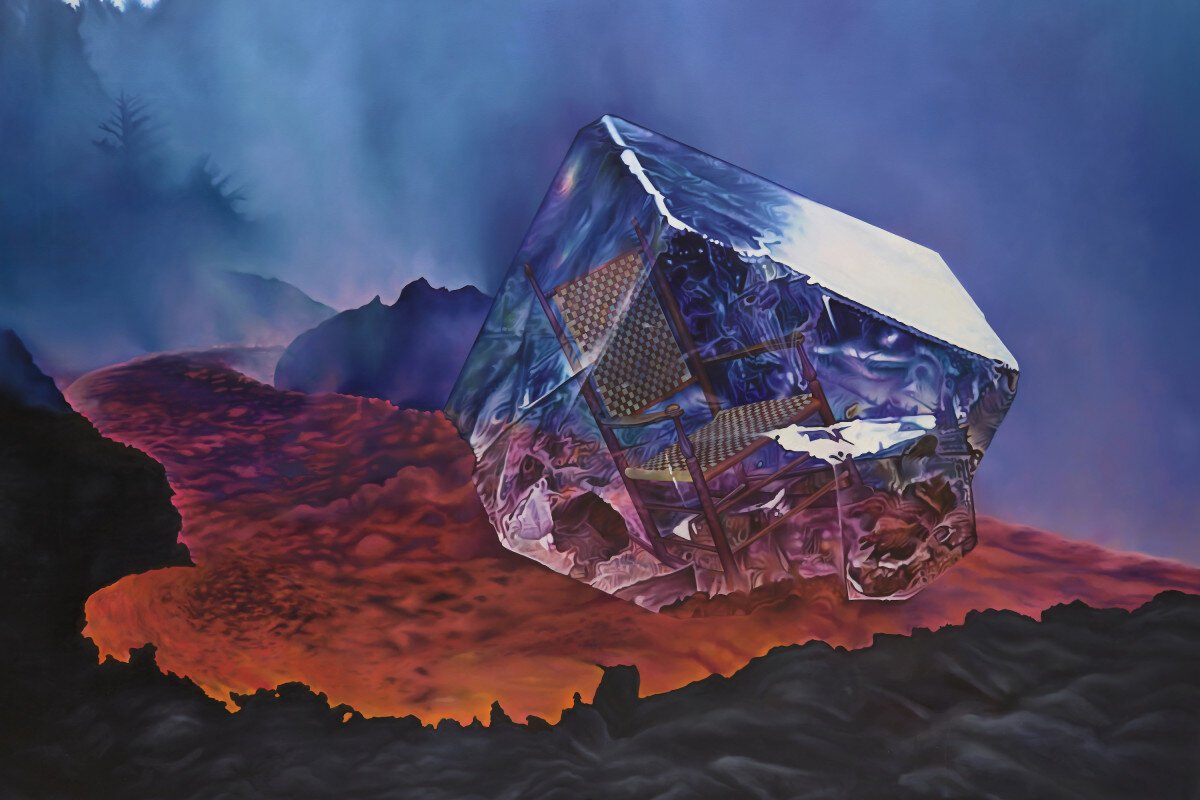

The galleries will in fact be filled with the smoke wafting from Evan Holloway’s incense holders, whose cylindrical forms–made from steel, plaster, clay, and other materials–also bear melancholic and slightly sinister stains left behind by the spent batteries used to create the characteristic circular openings in their surfaces. Holloway pits an avuncular, even hopeful otherworldliness against the unromantic facts of life on Earth in an era profoundly marked by the effects of industrial processes. The relationship between nature and artifice comes to the fore in works by Arlene Shechet, especially one in which a painted wood base supports ceramic forms that themselves appear to have been crafted by natural forces.

Throughout much of this exhibition, art follows the way of nature, guided by its innate compositional drives and responding to its sense of proportion. Barbara Chase-Riboud’s sculptures, made from ribbon-like lengths of bronze and silk cords, are poetic exercises in polarity. They combine extremes of hardness and softness, rigidity and flexibility, and structure and ornament, and not only suggest that the most powerful innovation might in fact be a radical act of synthesis, but remind us that the physical world in which we live is constantly inventing ways to unify and balance itself. Given that an instinct toward violent ideological polarity has become a defining feature of our species, perhaps Uranus’s transit through Taurus over the next seven years symbolizes the paradoxical shock that will accompany true harmony, if and when it comes. (Words and images via David Kordansky Gallery.)